Richard McKenna: A Hole Snipe's Writer

Taken from The Sand Pebbles Motion Picture Website - 7 years on the Web!

There are few writers that ever really gave Navy engineers their due. There are writers who give you a very good sense of what it's like to be at sea in the last century, Joseph Conrad, Nicholas Monsarrat, and Herman Wouk come to mind. But no one to my knowledge ever did justice to what it was like to be an engineer, except

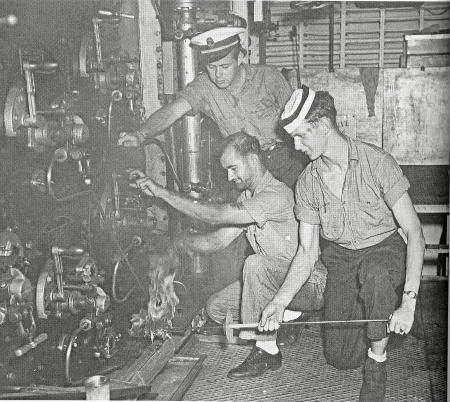

Richard McKenna. McKenna was a hole snipe. "Hole snipe" translates into someone who's a Navy operating engineer, which in this case means either a machinist mate or a boiler technician (today this would include enginemen and gas turbine technicians, and unlike in McKenna's day there are women in all of the engineering specialties), who spends most of his time in the "hole", which is what the engineering plant on a Navy ship is referred to. In McKenna's case he was a machinist mate, a snipe responsible for maintaining and operating the ship's main engines and its associated auxiliary equipment.

McKenna with fellow engineers, and alone. From: Richard McKenna - The Sand Pebbles

McKenna joined the Navy in 1931, during the Depression, to help his family financially. He stayed in the service through World War II and the better part of the Korean War, leaving the service after 22 years in 1953 at the age of 40. Using the G.I. Bill, which was the font of education for many a man coming out of the service after WW II and through the Vietnam War, he went onto the University of North Carolina; this is where he started to write to hone his skills. The book he's most famous for is The Sand Pebbles, which was also made into an excellent movie by the same name released in 1966 and starring Steve McQueen. A collection of McKenna's short stories and essays was put together in The Left-Handed Monkey Wrench: Stories and Essays , and as to be expected engineers are prominent in all of the short stories here. McKenna captured engineers in a way no one I've ever read did, bringing them into my imagination in a way that I, in my 22 years in the Navy and my many years working as and with engineers, had actually experienced them, and came to appreciate and respect them.

McKenna's characters are invariably outsiders, men dedicated to doing it correctly and in turn doing so in spite of what is otherwise expected by peers or society. In one of his short stories, "King's Horsemen", he writes about a ship on station in Chinese waters prior to WW II. A new machinist mate by the name of Hodos comes on board and he immediately stands apart because he doesn't fall in with the bad habits accumulated by a ship and crew far too long on foreign station - they've all gone "local" or "native" by virtue of their distance from the "real" Navy. The engineering plant is run by Dorsey Brown, a man who takes lavish and inappropriate pride in small things, has little true or holistic knowledge about his job and what it entails, and who otherwise encourages sycophants who may either hate or otherwise have little respect for him but are loathe to cross him. Hodos, a junior enlisted man, is totally the opposite of Brown, with simple needs, no care for what others think of him, and a love for the machines he's tasked to maintain and run. In the course of events Hodos undermines Brown, not by words but by actions and competence, and in the end he instills a pride in the engineers and the entire ship's crew by helping the ship do something it should have been able to do at any time had it been maintained properly. In the end, though, Hodos knows he needs to move on - paladins aren't well-suited to the company of mediocrity, especially when the mediocre are in charge.

McKenna took the theme from "King's Horsemen" and fleshed it out into what became "The Sand Pebbles". Hodos became Holman, and Dorsey Brown was replaced by a Chinese overseer of engineroom coolies that did all the actual physical labor on board the U.S.S. San Pablo; the crew of the San Pablo became the Sand Pebbles. In Horsemen Hodos takes under his wing a young enlisted man who's a pariah in the engineroom, teaching him what he needs to know to become a true engineer, not a "show" one like Brown, and imbues in him an appreciation that knowledge is what sets you free. Holman takes a Chinese coolie in tow, teaching him the why of things that before Holman he was only expected to imitate without truly knowing what or why he was doing what he did. In The Sand Pebbles we meet a crueler reality and ending for passing on knowledge, one where freedom isn't the end result as racial intolerance reigns and upsetting "rice bowls" is not to be tolerated. Regardless of the outcome Holman gives the coolie the dignity and respect deserved of any man, for this man was an engineer and therefore deserving an engineer's due, anything else, like race, was incidental and on the whole inconsequential.

Holman is a loner who's standard of excellence rubs many the wrong way, and ultimately in the end he's killed for those standards, and for the love of a missionary woman that the world, and surely her father believes was beyond the likes of a man like Holman - Holman in many ways understood the slights of the coolie from the experiences of his own life, as would have any Sailor prone to a modicum of reflection in this day. Of course a man like Holman is what every man should aspire to, but it's hard to be knowledgeable, confident, AND be able to stand up to mediocrity, ineptitude, or senseless prejudice to do what's right. My guess is that McKenna, as many Sailors in his day, often found himself judged for the uniform he wore and the job he did; he lived through a period when Sailors were still greeted with signs on store doors telling patrons that "Dogs and Sailors are not welcome".

McKenna's characters are all educated men, though not in the traditional sense of the word. Holman and Hodos were both driven to learn, either through books or the correspondence courses the Navy made available to its Sailors (McKenna himself is said to have taken many correspondence courses and has been quoted as saying that he, "... hid books in the nooks and crannies of ships 'the way a squirrel hides acorns.'"), and then through the "hands on" sort of experience essential for an engineer to truly learn and know the equipment he works with day in and day out. What sets McKenna's characters apart is the need to know, and the willingness to work hard to achieve that knowledge, characteristics one would be hard pressed not to believe were part of the makings of the writer himself.

In 1963 the novel "The Sand Pebbles" spent 28 weeks on the NY Times Bestseller list,

and the book earned McKenna the prestigious $10,000 Harper award. But novels are always for a relatively selective audience and an author has a great deal of latitude with regard to risk and what tastes that are appealed to with a book. In this sense the movie "The Sand Pebbles" was a much larger risk. By virtue of the star power emanating from the film with Steve McQueen, Candice Bergen, Richard Attenborough, Mako, and Richard Crenna, the film was guaranteed to get attention, but the ending wasn't the typical American movie fare where the norm was for the hero to overcome adversity and daunting odds and finally get the girl. In one sense it was a movie of the times with a very existential theme, not unlike Paul Newman's 1967 "Cool Hand Luke". (Interestingly enough McQueen was nominated for his first and only Academy Award for this movie, and Newman was nominated for his role as Luke, and both were passed over. It wasn't until Jack Nicholson's R.P. McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) that the great American anti-hero won big Hollywood recognition.) The story was driven by the existentialism of Holman, a man who was reflective and did what he felt was best in whatever situation he found himself in, and who stood by his convictions to the point of risking and finally giving up his own life.

McKenna died at the age of 51 while working on his second book. He was a gifted writer with an extraordinary sensitivity to the lives and pains of men who all too often don't get our attention, no doubt honed from his own experiences during his 22 years in the Navy, and to the difficult questions and situations many of us face in our lives. There were no simple answers in McKenna's world, and of course most important and valuable situations rarely ever demand simple solutions. It's clear from his work that he believed that a man without learning, without convictions, and without the ability and willingness to work hard will rarely make a positive difference in the unfolding theme of a life, and will not be up to the challenges of a life fully lived.

For more information about the movie be sure to visit:

The Sand Pebbles Motion Picture Website

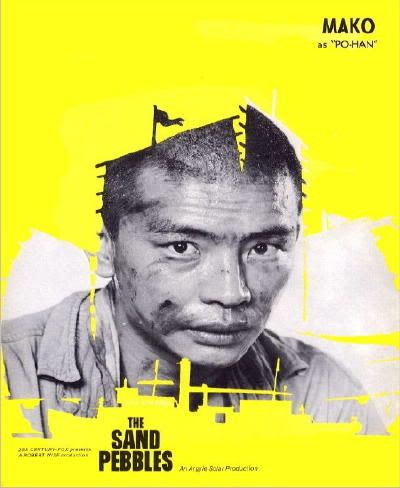

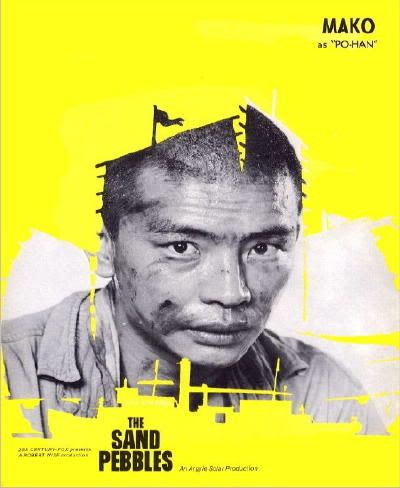

Addendum (7/25/06): Mako, who played Po-han, the Chinese coolie mentioned above, died last Friday (7/21/06). Mako was an excellent actor, his portrayal of Po-han earned him one of two Academy Award nominations, the other to Steve McQueen, for the movie. You can learn more about Mako at Mako, 72: Actor Opened Door for Asian Americans.