What Should We Be Teaching In HS Chemistry?

I doubt that there's a teacher for any subject that hasn't asked a question similar to the one addressed in the title to today's blog. They may not have been pondering chemistry but rather history, geography, math, etc., with specific regard to what it was that they should be focusing on to make for the best learning experience for their students, with the idea being to best prepare them for whatever future lies before them. This becomes a problem for many teachers, many of whom are convinced that what they know from their own past experience is what meets the need, though in the case of chemistry specifically there seems to be a disconnect between what high school instructors feel is important and what college instructors are looking for.

In chemistry there are two widely held perspectives regarding what the goal should be for a chemistry curriculum:

1. Preparing students for college chemistry.

2. Helping to mold a more scientifically aware and comfortable citizen.

Goal #2 is not divorced from goal #1, though when the curriculum focus is largely on prepping students for college chemistry (as opposed to just college) the emphasis that might otherwise be given to nurturing a more scientifically literate or aware citizen is very often subsumed, if not all together lost, in the quest for some ill-defined goal of college chemistry preparation. Deters (1) found that high school chemistry teachers were split about 50/50 on which of the two goals were most important.

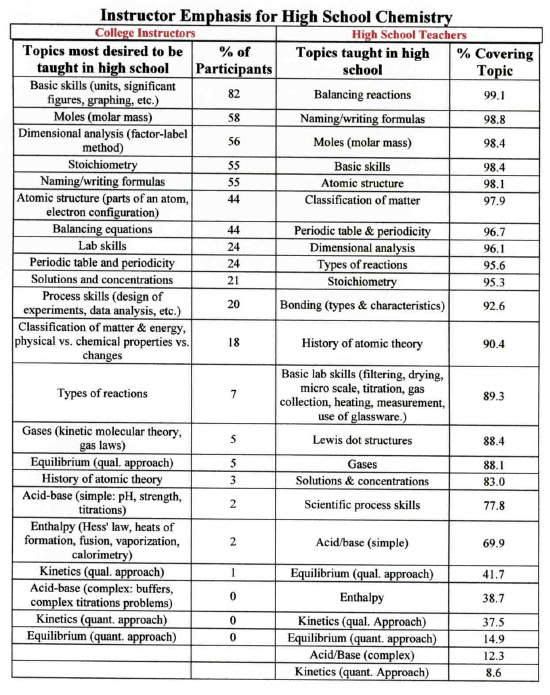

Specifically it is found (1 - 4) that while the goal may be to create students who are best prepared for college chemistry, what this requires is not determined in concert with college instructors but otherwise based on the assumptions and beliefs of high school teachers, various levels of state education administrators, parents, and school committees/districts. Efforts have been made to identify and better understand this problem (3 - 4) in the past, and most recently by Kelly Deters (1 - 2). The following chart is an amalgam of information provided by Deters (1 & 2) based on the results of surveys of college instructors and high school teachers presented similar lists of topics. The college instructors represent 96 of 300 attendees at the Biennial Conference on Chemical Education in August 2002 at The University of Michigan (2). The instructors were asked to choose the top 5 topics from a list provided (shown in the table to the left.) The high school teachers represent 571 teachers located throughout the country who were in contact with Deters from her first article (1) and were asked what topics within chemistry that they were teaching.

What's most striking is the divergence in topics considered to be important by both groups. A comparison of the two shows that there's clearly a disconnect between what college instructors desire and what high school teachers feel that they should be providing to their students. Deters shares with us: "These surveys showed that while the high school teachers focused on content and knowledge, the college professors tended to focus on personality traits, higher order thinking skills, study skills, and interest" (1).

Mitchell (3 - 4) approached the topic differently from Deters but came to many similar conclusions (it should be noted that Mitchell's survey population of college instructors was larger than Deters, about 280.) Mitchell found that college instructors were more concerned that high school students come into the college environment with good study habits, reading skills, basic math skills, and some measure of interest in and understanding of science: "Higher level instructors prefer that lower level instructors concentrate on teaching students how to study and think in general, leaving the development of a specific knowledge base about the subject to the "experts""(3). The following points come through in the references cited:

1. College instructors do not feel that high school chemistry should be a mini-version of a college chemistry course (3).

2. There's little value in emphasizing more intricate/difficult chemistry topics, i.e. content, inasmuch as students lose much (up to 70% within a year) of what they learn after leaving the course (1, 3). Deters (1) quotes Marvin Gold (5) on this subject: "My plea is that we (all of us, high school and college teachers alike) attempt to create a better balance between the teaching of content and the development of cognitive skills. The students who do not take college chemistry will forget almost all of the content. Those who take some college chemistry will begin to forget it unless it is applied to their own careers. Who needs to know a lot of content? Practicing chemists, that's who, and they will learn the content as they continue on in upper level courses and in the day to day practice of their profession."

3. The ability of students in high school (research indicates that one half or more students fall into this category) to successfully grapple with and grasp the more abstract aspects of chemistry is limited by their mental development at the age they normally encounter a course such as chemistry (1). While much of the basic material can be dealt with easily enough by the vast majority of students, the more abstruse topic areas can be problematic and result in frustration for the student concerned.

4. Teachers are trying to teach more than they're able to given the time constraints placed on them - Deters' results showed that 75% of teachers (a total of 571 found throughout the nation) participating in her survey are not able to cover all the topics they would like to in their courses. Given that a significant amount of what they are teaching is not considered by collegiate educators as important preparation for college level courses, the question arises as to whether teachers might find themselves more productively using their time focusing more on the basics, real-life applications of chemistry, and inquiry-based learning which in the long-term may well encourage students into science related fields professionally (1).

What we teach in high school is heavily influenced by what we've always done and an apparently mistaken belief, reflected in the content heavy curriculums of the science teachers surveyed, that heavily content laden courses are the best route for college prep of students. Deters (1) makes the following point:

"As many surveys of college professors indicate that content is less important than process skills, study skills, interest, and lack of fear in the subject, then high school teachers would better prepare their students by setting these as their goals and using content as the avenue through which to meet these goals."

Where the line should be drawn in content, how much emphasis should be placed on process skills, where inquiry-based teaching and learning should fit into the overall plan (Deters found that while most chemistry teachers believe this is an important tool in the teaching toolbox, about 45% of the teaching population is not using it (1)), how we should convince those in charge that, as Deters puts it, "... that less can be more ...", and how we can work to increase interest and reduce fear in chemistry in particular and science in general, all stand as some of the more pressing challenges for chemistry teachers today.

1. Deters, K. Accepted for and pending publication J. Chem. Educ. as of Aug 2005. What Are We Teaching in High School Chemistry?

2. Deters, K. J. Chem. Educ. 2003, 80,1153. What Should We Teach in High School hemistry?

3. Mitchell, T. J. Chem. Educ. 1989, 66, 563. What Do Instructors Expect from Beginning Chemistry Students? Part I

4. Mitchell, I. J. Chem. Educ. 1991, 68, 116. What Do Instructors Expect from Beginning Chemistry Students? Part II

5. Gold, M. J. Chem. Educ. 1988, 65, 781. Chemical Education: An Obsession with Content.

Note: Blogger is willing to send the articles (collectively about 1 megabyte) to anyone interested who sends an email request (not a request through the comment section of the blog) to science_teach(at)cox(dot)net.

9 Comments:

Well, I am biased, but I think a little more organic chemistry should be included in high school. I realize that only complicates matters, but it is what I think. I also think it is necessary to emphasize to students how important it is for them to be very good at algebra.

Too often, students who are not proficient in algebra are challenged unnecessarily by chemistry problems. That's because they actually have to solve two problems: the math problem, and the chemistry problem. If one attains sufficient math proficiency, the math part of the problem becomes transparent; this enables the student to focus on the chemistry.

Besides, proficiency in algebra is one of the factors that most strongly predicts success on standardized tests, if I remember correctly.

I think your best bet is to make friends with the math teachers. Also make friends with the local college chemistry instructors.

Anyway, you clearly are thinking a lot and preparing yourself well. I'm sure you'll do a great job.

Joseph,

With your math focus you're hitting on one of the areas that most trouble chemistry teachers. I'd say that there's not a chemistry teacher out there who'd tell you that in their average college prep and honors (yep, honors, it may not be so with AP chem students, but pretty much everyone else) there's a lack of ability to manipulate and use information mathematically.

This becomes a real prolbem inasmuch as the chemistry teacher is under the understanding that the student sitting in his or her class went through the requisite math for the chemistry course and therefore it shouldn't be their responsibility to teach math. Mathematical "comfort" and facility is one of those process skills that college instructors identify as being necessary, and chemistry is pretty much the first course many students enter where they're expected to use what they've learned in math, but many chemistry teachers balk at having to do what's supposedly done in another department.

Trying to pin down what should be included in basic HS chemistry is certainly the great challenge, and I agree that math is something that we need to spend more time on. Getting everyone else to see this and actually move in that direction is a whole other challenge.

WHen I was in college, I tutored the freshman Chemistry students. Some would come in and be able to do the math, and I usually could help them in 10 minutes. If they struggled witht he math, it was much more difficult.

I mentioned the thing about algebra and standardized testing, specifically because there now is so much emphasis on test scores in high school. Perhaps that information would motivate the HS administration to beef up the math instruction, if only to get better scores under the NCLB programs.

In my very limited experience and from what I'm reading, the math side of the house isn't necessarily planned with the science side in mind, and vice versa. At this point the math and reading types are the only ones having to sweat NCLB testing, though the science types will fall into this over the next two years here. You'd think at some point that the math and science concerns would merge into some form of concrete action, but I'm not seeing that nor have any inkling of this being an issue from this perspective. Maybe others are seeing it in their districts/states, and frankly I think it's a concern we need to all have, along with a plan to try and do something about it.

Ianbility to deal with math, especially exponents and logs was one of my biggest frustrations as a TA. This was highly correlated with the inability to read a word problem and set up an equation.

Shouldn't the HS curriculum differ slightly for different student groups? Those heading to AP Chem or AP Physics need a better grounding in math than those stopping with Chem I.

John,

There's no question that there needs to be differentiation of instruction and content for differing levels of students. The big problem by and large seems to be that no matter what level we're talking about of student, it seems that by the time they get to college and take similar courses they're deficient in the very skills you're mentioning here. This is so bad that to some degree I have to wonder if it's not just a matter of the students not getting it, but teachers not getting it as well, and in turn being unable to properly train their students.

Hi, guys!

Research that I read about indicates that there is very little transfer of math skills to science classes. It almost seems as if we must teach the math skills in a science context in order to give students the science skill that they need.

In addition, I'm dealing with the Massachusetts State Frameworks (sic) for Science and Technology (q.v.) The last time I checked, the term "mole" was not mentioned. They do revise these almost ev ery 6 months. I find that no normal class--not even honor--could cover these topics, even superficially, in a single class. Next year, our kids graduation will depend, in part, on their performance on the State MCAS tests, one of which will be science.

I wonder if the college instructors weighed in on the standards for HS Chemistry in the Frameworks? I tried, and failed, to be involved.

TIm Van Wey

Tim,

I'd have to see the studies regarding math skills to fully appreciate what it means that math skills are not transferred to science classes. My personal experience, while granted is not scientifically conducted research, shows me that those kids who are in calculus or trig by the time they enter my class are able to deal with the math that's attendant to a chemistry class. Those students, pretty much all in my "regular" chemistry class, who are in IMP, the Interactive Math Program, are unable easily to apply basic math skills to chemistry, and they, in turn, represent my highest drop/failure population of students. So experience shows me that those kids who are able to work through the math in their first two years and pretty much excel at it are in fact able to handle the math they're exposed to in chemistry.

I can identify with the difficult position of trying to balance what content the curriculum dictates while also trying to build basic skills. A couple points:

1. NY state has a large amount of information students must know for their state test, including Le Chatelier's principle, acid-base theories, etc.

2. At our school most students are lumped in the same first-year course, whether they have barely passed math or they plan on taking AP chem.

3. Want to be frustrated? Ask a first-year chemistry student to solve D = M / V for the volume. I'd say at least 1/3 of my students fail. And after a week of math review, they will continue to fail later in the year.

I would be very excited to spend less time on content and more on the excitement of science/chemistry if the state allowed. At least that chart gives ideas for what topics could be eliminated/truncated.

Post a Comment

<< Home