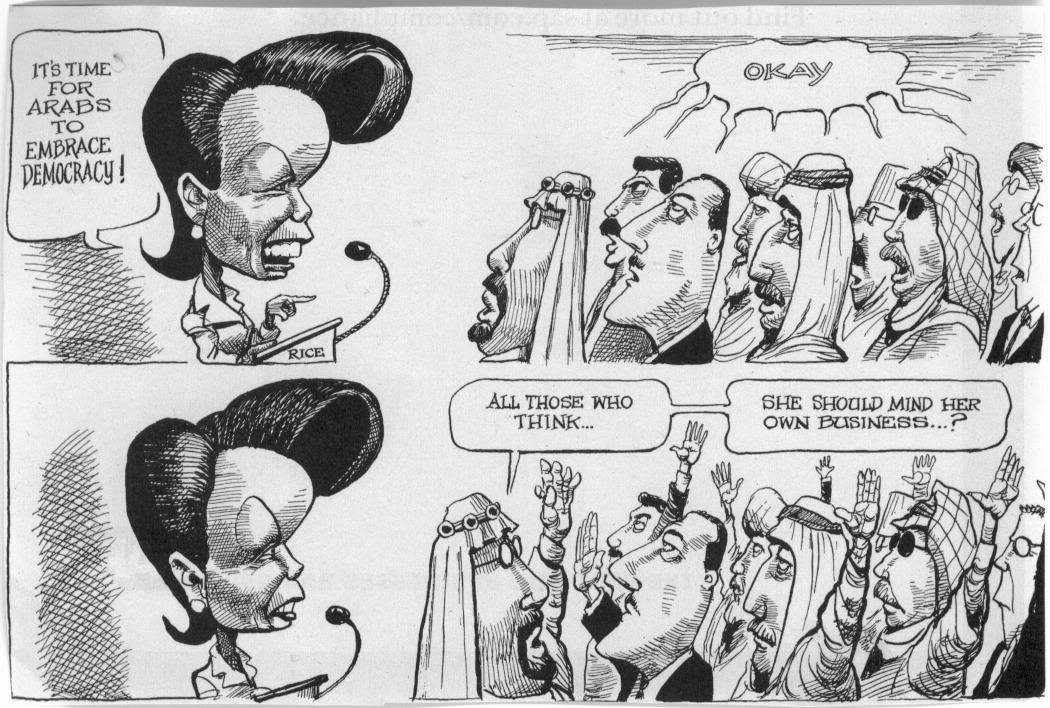

Courtesy of The Economist

Cartoon courtesy of The Economist, June 25 - July 1, 2005

This segues nicely with a recent article in the NY Times Magazine by Michael Ignatieff, a writer I respect a great deal and whose books have been no small source of neuronal stimulation. The article is Who Are Americans to Think That Freedom Is Theirs to Spread?. Ignatieff gets into a discussion regarding Jeffersonian democracy and how it's hard to argue that anyone wouldn't want to live in a country where such were the dominating philosophy of governance. I agree, I think everyone is entitled to democracy, and in keeping with that thought Ignatieff then goes onto argue that America is the only country that can in fact export democracy as we seem to be the only ones that believe so strongly in it that we on some level strive to help other countries establish their own democracies.

As always Ignatieff is interesting to read, though here he definitely gets things wrong in my view. He's focusing on the issue of this country exporting democracy as a casus belli for Iraq, and while I concede that this indeed was one of the reasons for our going into that country I feel it's obscured significantly by the way the war was sold to the American people. Many indeed would argue that we went into Iraq to export democracy, that we were going to establish the first democracy in the Middle East and the democracy meme/virus would spread far and wide, and all would be happy. In fact that's a very Jeffersonian perspective, as Ignatieff shares with us part of a piece written by Jefferson before his death:

Democracy's worldwide triumph was assured, he went on to say, because ''the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion'' would soon convince all men that they were born not to be ruled but to rule themselves in freedom.

And I agree, men and women are born to rule themselves --- I believe that, I honestly do. But it's not a meme that you can simply expect a culture to accept on its own, as we seem to expect now in Iraq. This meme grew here in the cauldron of an internal rebellion. We rebelled against what we perceived to be our oppressor at the time, Great Britain, and the rebellion was a well-thought out one, guided within the framework of striving towards an ideal of democracy. Fortunately for us that ideal took root and flourished, but it wasn't a sure thing at the time, nor was it so for a number of decades hence. Yet we're expecting that by simply saying that all men and women desire to be free, that this is a universal truth, that it will take wherever we plant it,

that it will be accepted, and we're the ones to make it so.

More to my main point, which is that Bush sold Iraq as a necessity for our national safety. There was a bad man with bad weapons and we didn't want to give him the chance to use those weapons on us. Moreover he was in cahoots with other bad men who had bad designs on this country. Sadaam must be stopped, was the cry. Of course Sadaam didn't have weapons (Thomas Powers does a wonderful breakdown of the intelligence failures tied to this in a NY Review of Books article, Secret Intelligence and the 'War on Terror', which, along with the questions surrounding the Downing Street memo, makes it hard to believe that Bush wasn't manipulating the facts to get us into Iraq), and there's not a shred of evidence to support that he was in cahoots with terrorists of any flavor, much less al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden.

So we went into Iraq because this country was threatened, so much so that the threat that we knew was gallivanting through the hills of Pakistan and Afghanistan was no longer the priority, Iraq now was because it was that much more of an important issue. Now, though, the administration is trying to sell us on the idea that we're actually traveling salesman of democracy, and it's costing us nearly 2,000 lives of our own, tens of thousands of Iraqi lives,

and over $200 billion in money for something that's so far removed from being a sure thing that it's not funny, in fact it's down right scary. But what's worse, we weren't sold on this idea from the start, it's plan B in Bush's list of reasons for doing what we're now doing and he hasn't admitted to any failure with regard to plan A, in fact everything's honky-dory on all fronts in Iraq if you're to believe him.

We've an administration that's essentially misguided, if not outright lied, to the American people, and we've damaged our credibility throughout the world. Is it any wonder that the countries we're most interested in trying to convince to change are more inclined to tell us to mind our own business than to listen to hypocritical lectures about changing how they do business?

2 Comments:

Something I definitely don't like about appeals to the Founding Fathers is that they tacitly are founded on those Founders' "inerrancy." Quite simply, I think Jefferson was wrong in that quote. We're not "born" to be anything, other than what we become.

This leads into something else, not only am I skeptical that we can "spread democracy," I'm also skeptical that democracy is sustainable. While the Roman Senate was hardly as democratic as our own institutions, isn't it remarkable that for many years the West lived under governments decidedly less democratic? The history of forms of government isn't some beautifully ascending line to democratic bliss. It is an up-and-down thing, with no regular pattern that can guaranty that this isn't the most democratic mankind will ever be.

Democracy doesn't survive because democracy is great (which it is), it survives because people don't feel desparate for something else. Given a catastrophe or severe economic depression, I have little doubt that any country, even ours, could dip into despotism.

An interesting perspective, not one I'm sure I agree with. In fact the Ignatieff article makes a point of highlighting the hypocrisy of Jefferson. The great man speaks for freedom but maintains, derives his comfort and sustenance from, and sleeps with slaves; Jefferson surely was in conflict with his ideals.

I don't see democracy as an experiment in human living as we now understand it until the 1700's starting with the French, and then growing on from there to us and onward. Democracy for the people by the people didn't exist in the time of the Romans or the Greeks, it was a highly selective venture in those olden days and they didn't have problems with slaves then, either.

It wasn't until we lifted the yoke of the Church, and gradually from there the yoke of emperors and kings, that we got to truly experience democracy as we now appreciate it. In that context I don't think democracy is that fragile a thing once people are accustomed to the idea, and its only real competition has failed miserably, to wit the form of Soviet communism that crumbled under its own weight.

I think there are certain conditions which allow for democracy to flourish and take root, and on the whole I think that most people would in fact agree that the aspirations of Jefferson are a good approximation of what most people indeed do want. The mix gets very complicated when religion is thrown into the batter and there is a large part of the problem in the Middle East. Democracy doesn't work very well in an environment of inequality and far too much of Islam is rooted in treating women specifically as second class citizens --- this gets in the way of any true democratic aspiration taking root.

I agree with you that any country can find itself falling into despotism if the conditions are right. But so far no true democracy has gone that route. Of course the experiment hasn't run for very long so there's a lot that remains to be seen, but I think on the whole that people do aspire to the freedoms we often take for granted here, but our trying to imbue those freedoms through our dedicated and to a degree forced efforts isn't the right way of trying to make this work. Maybe I'm wrong, but if I'm not then how this works will be rather unique in the context of all that's come before it.

Post a Comment

<< Home